The seventh in a series of posts on common but differentiated responsibilities. You can read the first here.

As we explored in an earlier post, economic growth over the last 30 years has generally exagerated wealth and emissions inequality within countries to the extent that such inequalities are often now more significant than those between countries. Climate justice thus requires a differentiation of responsibilities within countries as well as between them.

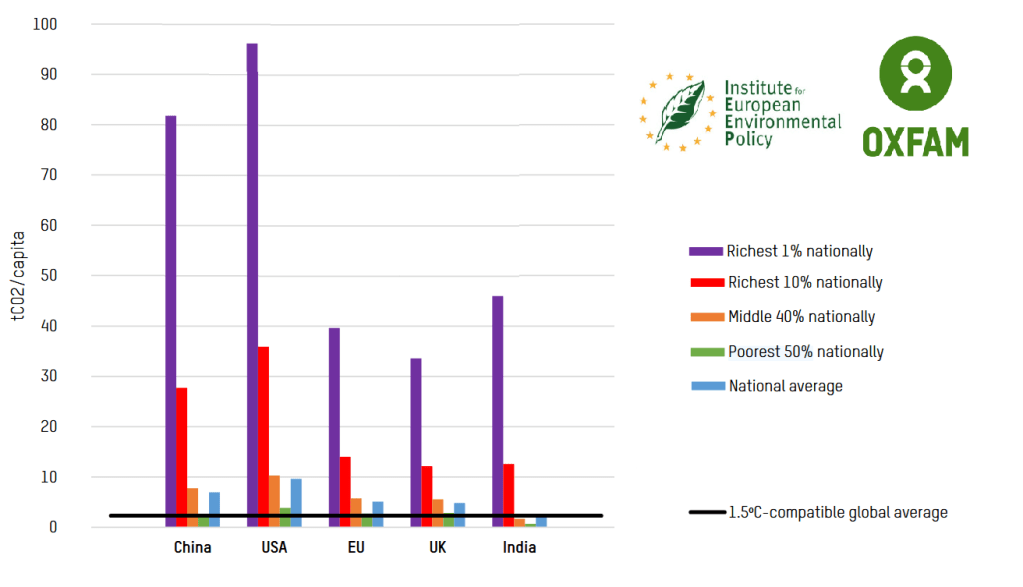

(Oxfam, 2021)

This is nicely illustrated in the figure above taken from a recent Oxfam report. In each of the featured countries, the poorest 50% of people will have emissions below that required for a 1.5° compatible global average. The richest 1% by contrast will have emissions of between 10 and 25 times this figure. If we assume that a just allocation of future emissions is an equal allocation of emissions (as we did between countries in the previous post), then this would require no action from the poorest 50% of people but a very significant reduction in the emissions for their richer compatriots.

Although the emissions for which the top 1% are responsible appear enormous in this figure, there are very few of them (1% – by definition!). When the number of people in each of the groups is taken into consideration, then it is the richest 10% who contribute more emissions than any of the others (considerably more than the richest 1% and a little bit more than the middle 40%). Whilst it would seem most obvious to target the 1%, effective action thus requires change within that top 10%.

There is a clear democratic deficit here in that a majority of people could vote to limit emissions to whithin the 1.5° compatible average by placing constraints on the personal emissions of the wealthy minority, without requiring to make any reductions themselves. The observation that there does not appear to be any substantial electoral demand for such legislation within any of the democracies represented in the figure above, suggests that democracy, as currently implemented in those countries, is not protecting the interests of the democratic majority.

One problem with seeking to impose such an approach within a globalised economy is that the wealthier high emitters have most freedom to travel. Enforcing strict limits on emissions within one country might result in wealthier citizens simply moving to other countries. Wealthier citizens may also emit greenhouse gases in countries other than that in which they live either while travelling or through buying products that have been made in other countries. Amongst the extremely rich, the emissions related to investment, which can be made anywhere in the world, are considerably more significant than emissions arising from lifestyle. There is thus a need for a global framework for concerted international action.

International agreement is generally devolved through the national parties rather than applying directly to individuals. Any international intitiative to curb emissions of the wealthy would need to operate by placing a responsibility on countries to reduce emissions inequality within their population and supporting them to do this. Doing this within the framework suggested in my last post could ensure a coherent approach to addressing climate justice both within and between countries.

As well as the issue of who should be required to reduce emissions is that of who should pay for mitigation, adaptation and any loss and damage. This is clearly tied even more directly to incomes than responsibility for emissions and consequently influenced by the trend of growing income inequality within countries . This can be exacebated by taxation which is generally lower on uneanered investment income than on earned income. Given the the wealthier you are, the more likely you are to have investments, wealthier individuals tend to be taxed at a lower effective rate, and many very highers earners structure their affairs to pay very little tax at all. Increasing tax rates on unearned income to match those on earned income, and ensuring that all income is taxed, might therefore be a just approach to levying climate finance.

A final issue here is that most analyses in this area tend to focus on income as a surrogate for wealth. Most taxation globally is on income and transactions, probably because flows of money are easier to identify and tax. Global wealth (estimated to be $450 trillion1) however, is approximately 4 times as much as Global GDP ($115 trillion). Over 47% of that global wealth is owned by individuals with a personal wealth of greater than $1 million. A recent report, by contrast, claims that the 55 countries that are most vulnerable to climate change have lost about £525 billion from the effects of climate change between 2000 and 2019. It is clear that quite modest wealth taxes on the world’s wealthiest people would comfortably cover those losses.

Much existing wealth has been created on the back of the industries that have been responsible for emitting those gases that have led to climate change and it would appear just that taxation of that wealth should be used as a tool for funding the damage that this has caused. That leads on, however, to a wider consderation of how the history of greenhouse gas emissions impacts on considerations of climate justice – the theme of the last post in this series which you can read at this link.

- A trillion is a thousand million. ↩︎