The fourth in a series of posts on common but differentiated responsibilities. You can read the first here.

The distribution of wealth is not the only thing that has changed since the language of common but differentiated responsibilites emerged. Our understanding of the science of climate change and its impacts has also changed radically since then.

The first report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was published in 1990, two years before the Rio Earth Summit. It stated “with certainty” that human emisisions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases were leading to global warming and “with confidence” that immediate and substantial reductions in those emissions would be required to stabilise concentrations at existing levels. The report predicted that warming would have impacts on agriculture and forstry, natural ecosystems, ocean and freshwater systems, human settlements and seasonal snow and ice cover, but presented little detail about what those impacts would be.

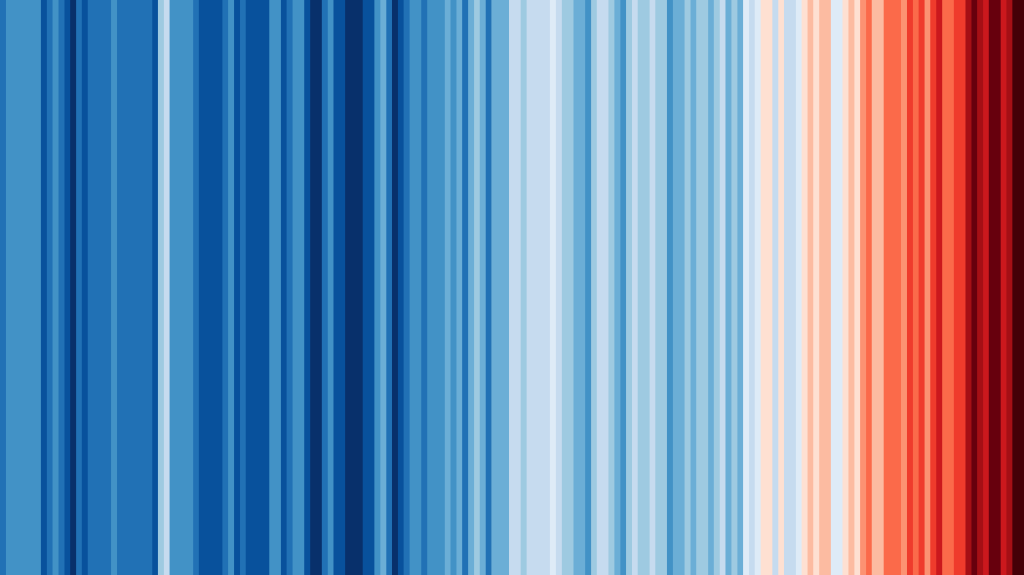

Since then a further five reports have been published. Each has confirmed the major findings of its predecessor and made predicitions about what the future holds with greater and greater precision. The more recent reports also include evidence that the predicitions of earlier reports have now been observed and present much more comprehensive descriptions of the future impacts of climate change. Without going into detail, the key finding of the most recent report in the context of climate justice is that the climate change that has already occured …

… has led to widespread adverse impacts and related losses and damages to nature and people . Vulnerable communities who have historically contributed the least to current climate change are disproportionately affected .

These adverse impacts and related losses and damages will escalate with every increment of global warming and long-term impacts are predicted to be “up to multiple times higher than currently observed”. Whilst vulnerable communities will continue to be disproportionately affected, there will be consequent global effects arising from to socio-economic development trends including migration, growing inequality and urbanisation.

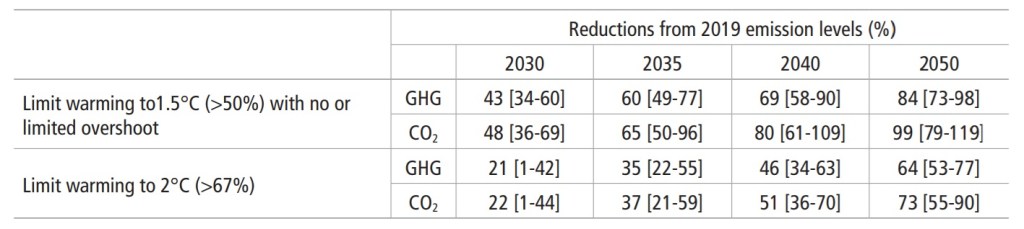

Whilst the reports make sober reading, they also provide increasingly clear guidance for the response that is required to limit further warning. In 2015 the Paris Climate Change Agreement, 195 countries (and the EU) committed to hold “the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels” and pursue efforts “to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.” The latest report defines carbon budgets, the maximum amount of carbon dioxide that can be emitted in order to meet these targets, and uses these to calculate the reductions that will be required gobally if they are to be met (see Table below).

These global reduction targets now provide a framework in which an increasing number of organisations can set targets for reducing the emissions for which they are responsible. A recent scientific paper from a group working at the University of Manchester within the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, for example, has proposed a methodology for downscaling the targets to sub-national areas and used it to set targets for local authorities across the UK. The Science Based Targets initiative provides an similar framework for setting coporate emissions reduction targets.

Both these take a pragmatic approach of “grandfathering”, assuming that an organisation’s emissions in 2019 provides a baseline and setting targets for reductions as a percentage of that baseline broadly in line with the table above. Although this seems reasonable in requiring those who are responsible for the most emissions to make the greatest reductions (in absolute terms) it takes no explicit account of other factors such as the relative value of the services that organisations provide, their capacity to make reductions or whether they had made substanital reductions already at the time the baseline was calculated. Despite this, for organisations working in developed economies, it appears a reasonable and practical approach towards reducing emissions.

The model is less applicable for setting targets that include developing economies in that it assumes that all responsibility for future emissions reduction is proportional to the level of baseline emissions. It makes no allowance1 for developing countries who might have low emissions and require to increase those emissions to meet acceptable development goals. In order for a just allocation of emissions targets, the approach will have to be modified to take into account those common but differentiated responsibilities within an overall framework that delivers the global emissions reductions required to meet the objectives of the Paris agreement.

You can read the next post in this series at this link.