The third in a series of posts on common but differentiated responsibilities. You can read the first here.

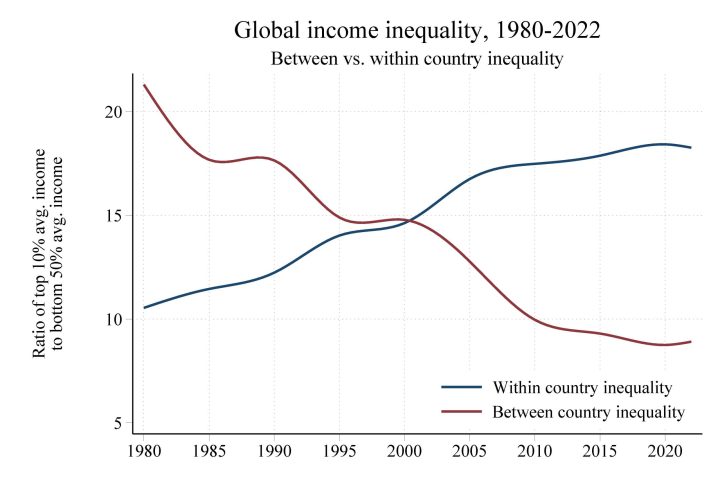

The world has changed markedly since the phrase “common but differentiated responsibilites” was first framed in 1994. It has changed even more markedly since the underlying concepts were first debated in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In those days the distribution of wealth and poverty across the world could quite reasonably be mapped geographically. Generally speaking whole countries could be classified as either rich or poor. This is reflected in the graph above which plots how inequality of income has changed over time. The left hand side of the graph shows the situation in the 1980s when income inequality within countries can be seen to be considerably less than income inequality between countries.

Over the past forty years strong economic growth, particularly in China and other countries in Asia, has considerably reduced the difference in income between countries. This is represented by the red line diminishing over time. Between country inequality is now about half what it was forty years ago (at least on this specific measure of inequality). At the same time the economic benefits of that growth have tended to benefit those who were already relatively wealthy much more than the general population in both rich and poor countries. Within country inequality has thus risen and is now approaching twice what it was in 1980, as represented by the blue line. To summarise, nowadays whether you are rich or poor depends much more on your economic status within a country than whether the country as a whole is rich or poor.

As carbon emissions (and other degrading effects on the planet) are stongly correlated to income, this changing pattern of income distribution affects the pattern of responsibility for those emissions. Indeed a graph of carbon emissions inequality against time (see below) shows very similar features to those of income distribution. As with income, whereas the carbon emissions that an individual is responsible used to be primarily dependent on which country they lived in, it is now determined much more by their economic status within that country.

This affects two of the three underlying issues that an understanding of common but differentiated responsibilities was evolved to address. Whereas responsibility for high current emissions used to be specific to a country as a whole, now it is far more determined by an individual’s economic status regardless of country. Indeed the emisisons of wealthy people in countries with weaker environmental protections may even be higher than in the countries that were labelled as “developed” at the time of the Rio Earth Summit. Similarly wealthy people are likely to have resources that make them more resilient to the effects of climate change regardless of the country in which they are living (although those living in countries with well developed infrastructure are likley to be relatively more resilient).

There is thus a strong argument that globally there are still common but differentiated responsibilites for carbon emissions, but that these are no longer defined by national boundaries. This would suggest that strategies for emission reduction should be differentiated within countries as well as between them. The focus should be on reducing the emissions attributable to the affluent wherever they live.

There are dangers in such an approach. The most obvious is that it contributes to a narrative that emissions are best attributed to indiviudals rather than countries and that this might erode the current assumption that responsibility for taking action rests at a national level. Individual countries still have to be made accountable for the emissions of all their inhabitants otherwise there will be no accountability at all.

Another risk in focussing on these summary measures of inequality is that the economic development has been uneven. The general trend of a reduction in between country inequality has largely been driven by a growing number of countries that have benefiited from siginificant economic growth over the last four decades. There are still substantial areas of the world that have been relatively unaffected, however, and where entire countries can still be meaningfully categorised as poor. These countries have correspondingly low emissions (per capita). They are also generally in the regions of the world (Africa, South and Central America, the Caribbean and parts of Asia) likely to experience the greatest effects of climate change. Their poverty will render them least resilient to deal with these. The language of common but differentiated responsibilities evolved, in part, to facilitate development in such countries by protecting them from the costs (financial and other) of emissions limitation and reduction. This needs to be preserved to allow that essential development to continue.

In summary, the concept of common but differentiated responsibilities to protect the climate system is as relevant today as it was in 1994. The way those differentiated responsibilities should be allocated, however, has changed considerably. Levels of income and emissions inequality within countries has risen considerably, and the concept of common but differentiated responsibilities needs to be applied within countries as well as between them. Given the sovereignty of individual countries, this should still be recognised as a responsibility of those countries. This is particularly true of countries originally labelled “developed” and also applies to many emerging economies. There are still a signficant number of countries which have benefitted little from economic growth and are still characterised by poverty. Differentiation of responsibilites at a national level remains essential to faciliate their development.

You can read the next post in this series at this link.

Sources

3 ways to look at global income inequality in 2023 – Insights from the World Inequality Database.

Chancel, L, P Bothe, and T Voituriez. Climate Inequality Report 2023. Paris: World Inequality Lab, 2023.

Who Has Contributed Most to Global CO2 Emissions? Our World in Data.

Deshmukh, Anshool. ‘Visualizing Global Per Capita CO2 Emissions’. Visual Capitalist, 2021.

One thought on “How relevant are “common but differentiated responsibilities” today?”