The second in a series of posts on common but differentiated responsibilities. You can read the first here.

Concerns about the effect that greenhouse gases were having on the climate led the UN General Assembly to endorse the creation of the Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change in 1988. It published its first report in 1990 which concluded that:

emissions resulting from human activities are substantially increasing the atmospheric concentrations of the greenhouse gases …[ which] … will enhance the greenhouse effect, resulting, on average, in an additional warming of the Earth’s surface.

It also included a brief section (3.1) describing the “common but varied responsibilities” of developed1 and developing countries in dealing with this challenge.

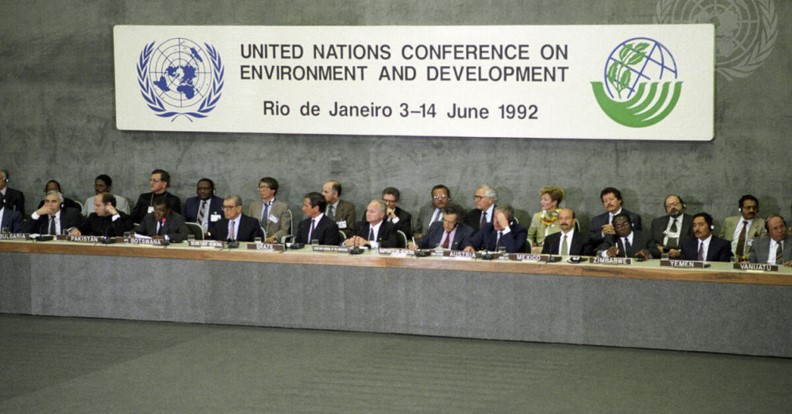

Following this, an intergovernmental negotiating committee met in New York in early 1992 to draft a document to be launched later that year at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. It was in this document, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), that the exact phrase “common but differentiated responsibilities” first occured 154 countries signed up, and the Convention entered into force in March 1994.

The concept of common but differentiated responsibilities, however, has roots going back much earlier. General concerns over depletion of natural resources and pollution arose in the 1940s, long before specific concerns about climate change. These concerns increased through the 1950s and 60s and in 1968 the United Nations General Assembly announced a Conference on the Human Environment, to be held in Stockholm in 1972. Later, this came to be referred to as the First Earth Summit and was characterised by considerable tension between the developed and developing countries.

The UN had been founded in 1945 by 51 countries, largely in Europe and the Americas, as a response to the Second World War and the resulting East-West split. By 1968, however, the entry of many newly independent former colonies across Africa and Asia had more than doubled membership. The needs of these poorer countries had been acknowledged by the UN’s first Development Decade (1961-70) and the founding of the UN Development Programme (UNDP) in 1966 strengthening their cohesion and ambitions within the UN. These were reinforced by China, which generally sided with developing countries. The Conference was its first major meeting after taking over the UN seat from Taiwan. With detente following the Cuban missile crisis of 1962 leading to a relative thawing in East-West relations, it was the relationship between the developed North and developing South that dominated the proceedings leading up to and at Stockholm.

The developed countries, led by Sweden, had called for the conference and assumed that it would focus exclusively on environmental protection as a universal concern. The draft agenda thus made no mention of development. Developing countries saw this concern for the environment as a luxury of the rich which would divert attention and resources from their own development needs. Led by the Brazilian delegation, they argued that these needs should be included in the Conference agenda and threatened a boycott . It was clear to all that the the greatest single threat to the environment was the global South following the same destructive path to industrialisation as the developed North, so the participation of developing countries was essential. Maurice Strong, the Secretary General of the Conference, thus convened a panel of 27 experts from both North and South to meet at a Founex, a small mountain village in Switzerland in the summer of 1971 to forge an approach acceptable to both sides.

The resulting Founex Report is a substantial document, but three new viewpoints are particularly important:

1. Whereas pollution in the developed world had largely been a result of development, pollution in the developing world had often been a consequence of the lack of choice arising from poverty and under-development. Economic development is thus essential to protect the environment in developing nations.

2. Developing nations cannot be expected to forego the development that developed countries have already benefitted from to protect the environment. Alternative approaches will be required that permit both development and environmental protection.

3.Developing countries do not generally have the financial and technical resources for development compatible with environmental protection. They are therefore entitled to expect financial and technical support from developed countries where they are available.

In the wake of the Report, the developing nations followed the lead of India’s Prime Minister Indira Ghandi and agreed to participate. In all the Conference was attended by 113 state delegations, along with representatives and observers from several UN agencies and a selection of non-governmental and inter-governmental organisations. Although the Warsaw Pact countries boycotted the conference over an argument about the exclusion of East Germany, the Conference Secretariat corresponded regularly with the Soviet embassy in Stockholm and incorporated feedback informally into the Conference outputs. The Conference was still divided by tensions between developed and developing nations but did largely reflect the agreement that had been established at Founex.

As a consequence the Stockholm Declaration acknowledged, amongst other things, that economic and social development is essential for ensuring environmental protection (Principle 8), that future environmental policies should not restrict the development potential of developing countries (Principle 11), that developing countries are entitled to adequate earnings for primary materials and raw commodities (Principle 10), and to substantial financial and technical support for development (Principle 9).

Although the wording is somewhat different, it is clear that the language of the UNFCCC and the principles of common but differentiated responsibility are deeply rooted in that of Founex Report and the Stockholm Declaration from 20 years earlier.

Read the next post in this series at this link.

Sources:

Brighton, C. 2017. Unlikely bedfellows, the evolution of the relationship between environmental protection and development. International and Comparative Law Quarterly 66(1):209-233.

Selin, H and Linner, B-O. 2005. The quest for global sustainability: international efforts on linking environment and development. CID Graduate Student and Postdoctoral Fellow Working Paper Series.

- Although the division of the world into developing and developed countries is generally regarded as outdated, the terms will be used here as they are those used in much of the historical literature on which these posts are based. ↩︎