The first of series of posts exploring the concept of common but differentiated responsibilities. 1

“Common but differentiated responsibilities”, often abbreviated as CBDR (or even CBDRRC for “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities”) , is a phrase that was embedded in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) which was launched at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. Article 3 commits countries who sign the convention (known as parties) to …

…protect the climate system for the benefit of present and future generations of humankind, on the basis of equity and in accordance with their common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities. Accordingly, the developed country Parties should take the lead in combating climate change and the adverse effects thereof.

It is a statement of the fundamental principal of what we now call “climate justice”. It acknowledges that addressing climate change is a common responsibility that we all share, but that we do not share equally. Developed countries bear more of the responsibility for three reasons:

1. the lifestyles of their generally wealthier citizens place more pressures on the global environment than those of the citizens of developing countries,

2. they have been doing this for much longer than developing countries and thus have had a much greater cumulative effect,

3. they have much greater financial and technical resources available than the developing countries. In this context its also important to remember that those financial resources are, at least in part, a consequence of how developing countries were exploited in the colonial period and since.

Just in case there was any uncertainty, an annex to the Convention lists 25 parties which were considered “developed”, and a further 11 listed as undergoing “the process of transitioning to a market economy”2

The principal is important because if embeds the concept of justice into environmental law placing an obligation on developed countries to help undeveloped countries. This is quite different from other aspects of international law where there is no requirement for developed countries to give assistance to developing countries. Developed countries may choose to offer aid of different kinds, but do so as an act of generosity rather than an obligation.

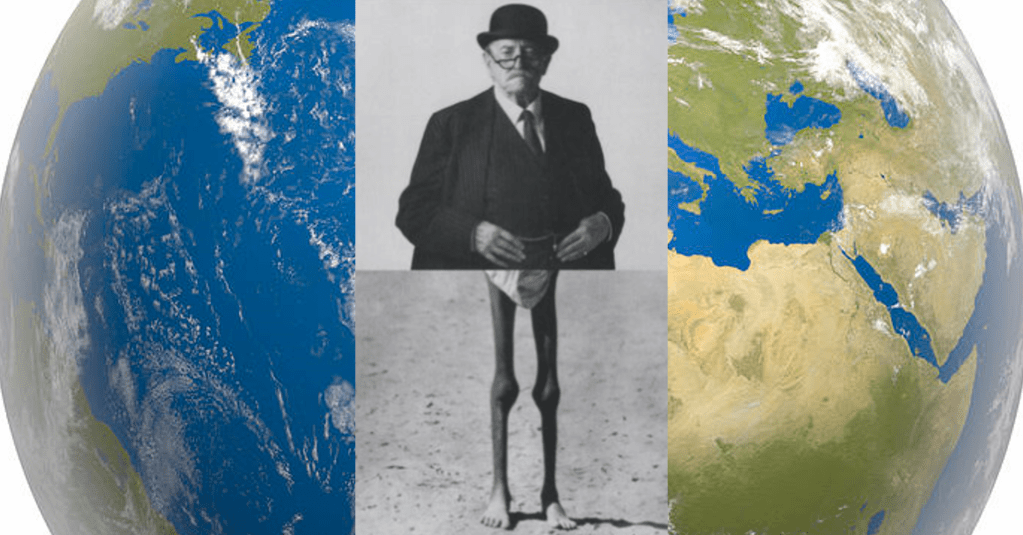

The picture at the top of this post is taken from a Christian Aid advert from the 1980s and in many ways summarises the meaning of the phrase. We all live on the same planet and have responsibilities to protect it for ourselves and future generations. But people in developed and developing countries live in very differently ways and have different resources available. As a consequence, those of us in developed countries have a much greater responsibility to take the lead in combatting climate change.

Read the next post in this series at this link.

- Although the division of the world into developing and developed countries is generally regarded as outdated, the terms will be used here as they are those used in much of the historical literature on which these posts are based. ↩︎

- The 24 “developed” countries were listed as Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, United Kingdom and the United States of America (and the European Economic Communitywas also listed). The 11 listed as undergoing “the process of transitioning to a market economy” were Belarus, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Russian Federation, Ukraine. ↩︎